BHCC Magazine - Spring/Summer 2021

Features

| 7 | Congratulations to Power Utility Program Graduates EPUT program alumni pursue goals in the energy industry |

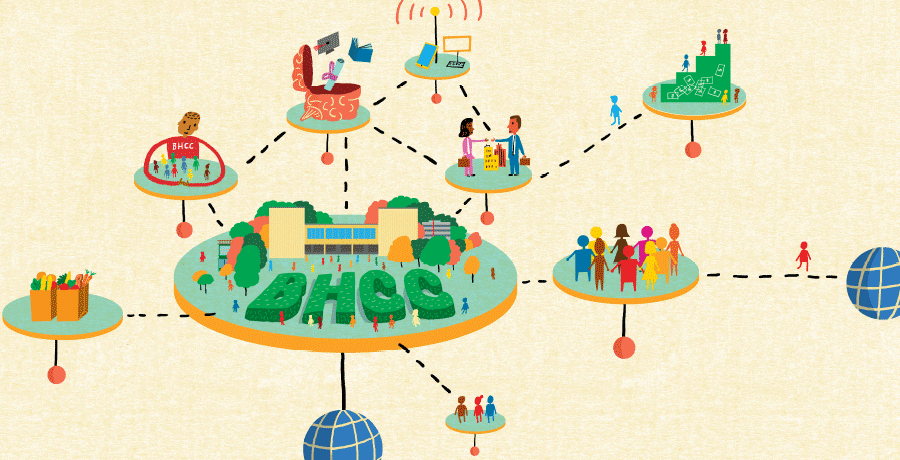

| 10 | Unlocking Potential The Vision of the Community College Hub |

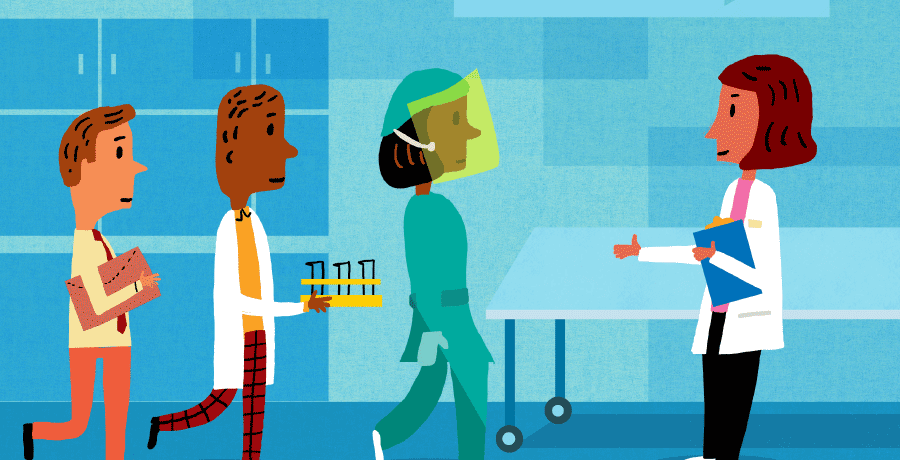

| 16 | Workforce Development Programs Meet Industry Demands Short-term training programs connect employers with skilled workers |

| 20 | Internship Pipeline Lessens Equity Gap STEM Internship Initiative expands paid opportunities for BHCC students |

| 24 | Dream Job BHCC students and alumni turn passions into purpose |